FAQ

The E&N has a 140 year history, and debates around repurposing the tracks have persisted for decades. Learn more about the Island Rail Corridor, FORT-VI, and more by clicking the questions below.

Questions about the Trail

Rail with a trail could be the best of both worlds, if funds were unlimited. Indeed, regional districts have already paid to build 47 km of unconnected trails next to the E&N tracks.

North of Duncan most of these new sections of trails did not require expensive bridges or work in wetland habitats. To create a continuous trail while preserving the tracks for train traffic, these new trails must be built beside the varied terrain of the railbed at much higher cost:

- 40 bridges between Langford and Courtenay would need to be twinned or upgraded. These span a total of 2.1km of bridges.

- Another 19 bridges from Parksville to Port Alberni would also need major upgrading

- The 45m Malahat Tunnel would need to be enlarged or have a trail built skirting Tunnel Mountain.

Excluding the cost of rehabilitating the railbed, the cost of a trail alongside the rail is likely to be $2-3 million per km from Langford north.

The danger is that a trail would simply not get built while tracks remain on the railbed. It has taken $36 million for a trail to be built beside the rails between Vic West and Langford, a project started in 2006 and still not completed. Follow this link for more information about the complicated and expensive process on the CRD website.

Putting the trail on the railbed will be orders of magnitude cheaper than putting one beside the tracks. Furthermore, a trail does not preclude establishing rail service in the future should that become economically viable.

First Nations are crucially important on this issue and must be involved in decisions of how to manage the Island Corridor for the future.

Some First Nations groups have asked to have the Corridor lands returned to them. Others are interested in the idea of a trail as a linear park through their community.

FORT-VI is dedicated to the reconciliation process and supports working with First Nations members to provide trail developments that are respectful of their needs. This includes helping create economic opportunities for First Nations along a future trail or re-routing the trail around First Nations land where requested.

Trains may reduce traffic but they are not expected to meaningfully eliminate congestion on the Malahat highway.* We advocate that funds which could have been spent on the train be dedicated to a fleet of electric buses. The $431 million needed to rehabilitate the train line could buy more than 300 electric buses that would reduce traffic and provide climate-friendly public transportation across the Island - including The Malahat.

It is also possible that the new trail could be used for emergency use over the Malahat. If the bridges are strengthened and the trail is sufficiently wide, ambulances, police vehicles or blocked cars could potentially drive on the trail in time of need. A train line would not have this kind of flexibility.

* Trans-Canada Highway 1 - Malahat Corridor Study Appendix K, July 2007 (Halcrow Consulting)

Train transportation is a form of mass transit that can reduce greenhouse gases in or between urban areas which fill trains. However, most proposals for renewed rail service on the Corridor include diesel-powered trains that are low frequency. For passenger rail to be efficient, trains must be full and use the fixed assets (rebuilt railway) as much as possible. In short, the trains must draw passengers from more fuel intensive modes. Island rail corridor train proposals do not achieve this.

In every case where Rail to Trail has been completed, the end result is no added carbon emissions from motorised transport and a more natural environment for the enjoyment of all. The overall carbon burden of rail construction is also much greater than using natural materials like crushed stone for trail construction.

Economic impact studies document how local businesses along trails benefit from an influx of visitors. They also significantly improve municipal tax revenues.

Trails also support BC's Tourism strategy to sustainably grow the local and visitor economy while respecting the environment. The Island Rail Corridor passes through 21 different communities that are an average of 11 km apart. These distances are readily traveled by bike, especially e-bikes.

Numerous small businesses stand to benefit from a Corridor trail:

- Restaurants and Pubs

- Retail stores

- Campgrounds

- First Nations businesses

- Snack shops

- Lodgings (Hotels, B&B, Airbnb)

- Tour guiding and bicycle tours

A similar trail, the Great Allegheny Passage, generates around $121 Million in annual economic impact and has created more than 1300 jobs. Other rail-to-trail projects demonstrate similar results. For a majority of trails, the economic benefits generated by trails far outweigh the cost of trail construction and maintenance.

Trail construction involves removing rails and ties, grading, and then spreading surface material.

The work starts with sampling at intervals to determine whether hazardous material needs special disposal and treatment.

Pulling up existing rails occurs next. The salvage value of the rails is considerable, helping to offset the cost of their removal.

The multi-use trail then requires additions such as surface material, decking and railings at bridges and trestles, bollards at road crossings, fencing, signage, and picnic facilities. Cost estimates for this work depend on type of surface chosen, extent of amenities and level of volunteerism in each community.

Once the work is done, ongoing costs of maintaining the trail would include vegetation control, periodic remediation of surface, graffiti and garbage removal. Leases and other non-rail income would be used to help offset these expenses.

No. The steepest grades are less than 3%. Walkers and riders will barely know they are ascending or descending. Crossing the Malahat on the trail won't require the heroics of those who brave the Malahat (or the Trans Canada Trail which bypasses the Malahat) on foot or by bike today.

Electric assist bikes will be allowed on the non-motorised trail depending on bylaws. In provincial parks, class 2 e-bikes are no longer permitted. Class 2 e-bikes were recently permitted on the Okanagan Rail Trail. Find here the ICBC requirements for electric bicycles.

Questions about re-establishing rail service

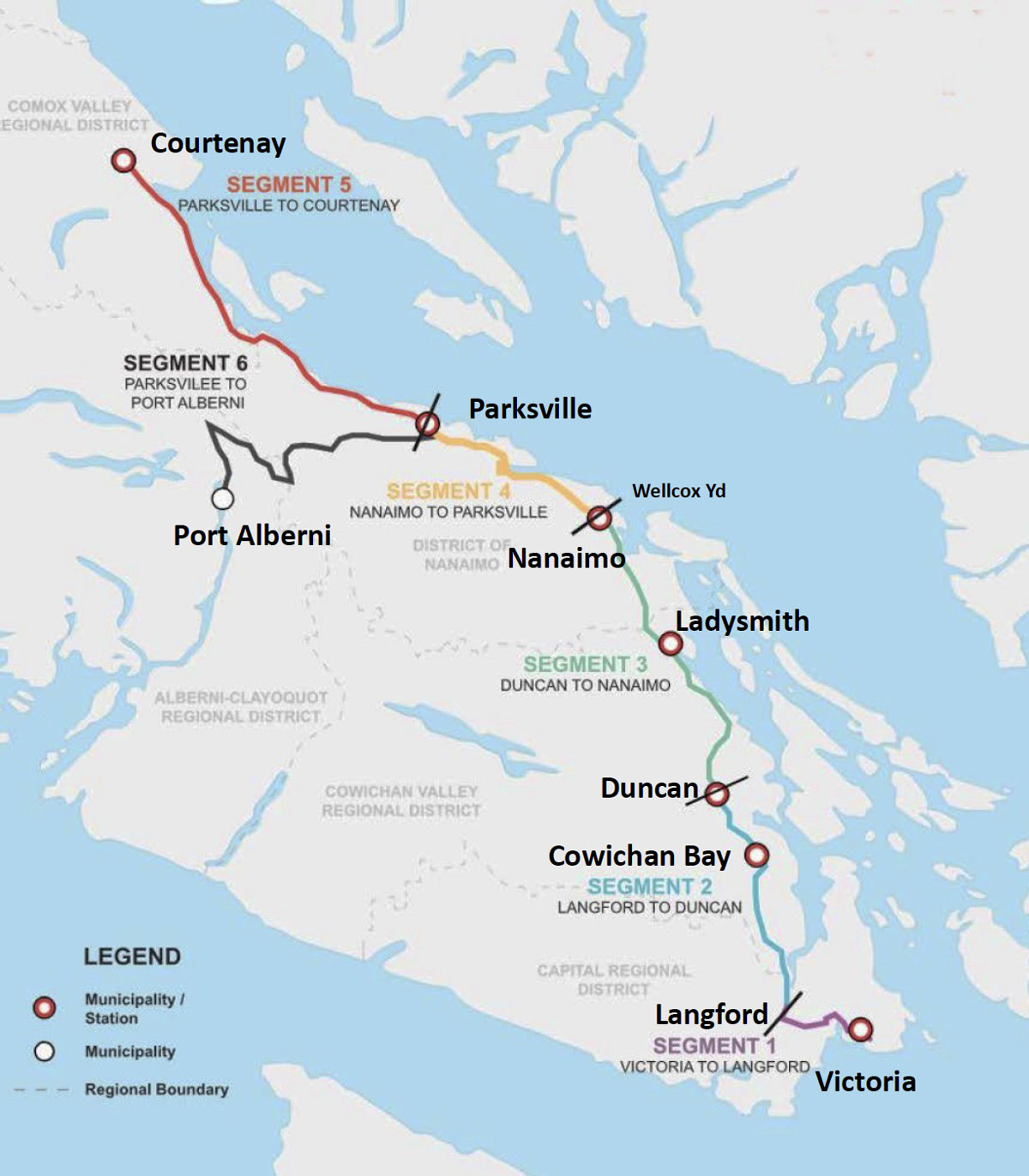

The main section of the Island Rail Corridor is 225 kilometres long from Victoria to Courtenay. A branch line stretches from Parksville to Port Alberni and is 64 kilometres long for a total of 289 km of mainline track.

The main section of the Island Rail Corridor is 225 kilometres long from Victoria to Courtenay. A branch line stretches from Parksville to Port Alberni and is 64 kilometres long for a total of 289 km of mainline track.

- 225 km rail corridor from Victoria to Courtenay (207 km from Langford to Courtenay)

- 64 km spur from Parksville to Port Alberni

- 5 Regional Districts and 14 First Nations

- 67 Bridges and Trestles

- 236 level crossings

Passenger service between Courtenay and Victoria stopped in 2011. The service was discontinued due to safety concerns about the quality of the tracks and the stability of many bridges along the line.

When the passenger service was running, VIA Rail provided an annual subsidy of $1.4 million due to low ridership.

A limited amount of industrial freight transport still continues on a short section of the tracks near Nanaimo.

No. According to the 1994 Supreme Court case between British Columbia (Attorney General) v. Canada (Attorney General) on whether Canada owes BC a constitutional obligation to ensure operation of rail service between Victoria and Nanaimo the ruling was that "Canada does not owe a constitutional obligation to British Columbia in respect of the operation of the Victoria to Nanaimo Vancouver Island rail line." See the Supreme Court of Canada Report 1994 [2SCR 41]

First Nations are crucially important on this issue and must be involved in decisions of how to manage the rail right of way for the future.

The history of rail construction on First Nations land is not pleasant. In many cases, the E&N railroad cut directly through the First Nations reserves, dividing their already small allotments and creating noise pollution in the community.

We have been in touch with various First Nations leaders about their opinion of renewed rail service. Some First Nations wish to have the rail lands given back to their reserve and others prefer an unbroken corridor. Ten acres of the Corridor were recently returned to the Snaw-Naw-As First Nation following their court case. Representatives from several First Nations sit on the Island Corridor Foundation (ICF) board, which owns the corridor, but five of them resigned recently when the board narrowly voted down their motion to look at alternative uses for the corridor.

No. The current condition of the tracks and railbed has deteriorated to the point that much of it is unusable. Furthermore, the Island Rail Corridor was designed for 19th Century low-speed freight transport of logs and coal.

The track is particularly curvy and has to reduce speed to cross roads or driveways in more than 230 locations. The E&N tracks were simply not made for bullet trains!

Estimates vary but all agree that rebuilding the full railway will incur significant expense. According to a 2020 BC Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure report, costs for the intermediate case include:

- $377 Million in estimated costs for Langford to Courtenay

Cost per Kilometer: $1.8 Million for just one train per day - $145 Million in estimated costs for Parksville to Port Alberni

Cost per km: $2.3 Million

This level of spending seems inordinate relative to other budgetary priorities at a local, provincial and federal level.

Relatedly, any profits from freight use of a restored railway are obligated to a US company, Southern Rail of Vancouver Island (SVI), and will not remain in the community.

Probably not. The original railway is curvy and was designed for low speed freight transportation in the 19th Century and is unsuitable for higher-speed commuter use.

The maximum allowable speed is 65 km per hour, slowing to 30 kmh on sections of the Malahat.* When passenger rail service was in operation, it took 90 minutes longer than driving the total route due to speed restrictions (uncontrolled crossings, track conditions, etc).

The initial phase would have travel time from Victoria to Courtenay at 5hr 11min (30 mph / 65 km/h). Completely rebuilding the tracks would improve these lengthy travel times to 3h 8min averaging 50mph / 80 km/h. This would be at great expense, and still not offer significant time savings compared to car or even electric bus transportation, especially if not point to point at locations on the track.

* Island Rail Corridor Condition Assessment, Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure, March 2020 (WSP)

Yes, but electrification was considered too costly in 2020 provincial studies.

Electrification was deemed too costly in Appendix I of the Island Rail Corridor Condition Assessment (March, 2020). Whether overhead lines (catenary system) or a third rail, the passenger and freight numbers did not warrant the expense.

Battery-powered trains may be available in the future, but likely no sooner than widespread electrically powered trucks and buses. The more plausible scenario is that the trains will run on diesel fuel, continuing to generate greenhouse gas emissions.

Unlikely. The South Island Transportation Study showed much better greenhouse gas reduction by buses on bus lanes between Langford and Vic West. Buses north over the Malahat would likely also show much better greenhouse gas reduction than diesel trains because of the higher frequency and flexibility of buses, encouraging greater ridership. The number of electric cars is growing rapidly, and will soon be mandated, and electric buses will soon be operating.

Questions about FORT-VI

Friends of Rails to Trails - Vancouver Island

No. Many of our members long advocated for rail service to be re-established on the Island Rail Corridor. Eventually they realized that rebuilding the tracks was prohibitively expensive and impractical. While politicians delayed, the lovely expanse of the corridor was falling into corrosion and decay.

If sufficient funding and ridership ever become available to restart rail service, FORT-VI is not opposed to switching the trail to a train line again.

Questions about the E&N

1884-1888: Rail service was built from Victoria to Courtenay by Robert Dunsmuir to support the coal and lumber industries and Esquimalt Naval Base. The last spike driven in was made of gold and the hammer was silver.

1905-1999: The E&N Railway was owned and operated by the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). At its peak, the railroad had 45 stations on the main line, 36 stations on the Cowichan line, and 8 stations on the Port Alberni line. At one time, approximately 8,500 carloads of forest and paper products, minerals, and chemicals were transported by the Southern Vancouver Island Railway each year.

2005: The Island Corridor Foundation (ICF) acquired the rail corridor in exchange for tax credits of $360 million to CPR with a vision to preserve the entire continguous corridor.

2011: Passenger rail service was discontinued due to safety concerns.

The Island Corridor Foundation (ICF).

They are the same. The Island Rail Corridor is the new name for what was previously the Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway (E&N Railway).

Questions about the Island Corridor Foundation (ICF)

The ICF was founded in 2003 as a non-profit society and registered as a charity in 2004. Members include 14 First Nations and 5 Regional Districts along the railway right of way.

The ICF should be applauded for preserving the full rail corridor up until today. By contrast, many other Canadian rail corridors - including some on Vancouver Island - have been sectioned off and sold.

For the past decade, the ICF has largely been concerned with restarting train service. But their stated vision goes beyond restoring the rails, as they exist "to preserve and use the corridor in perpetuity as one continuous corridor to connect and benefit all Island communities and First Nations along the corridor."

Canada Pacific Railway sold the corridor to the ICF for one dollar in 2006, receiving credit for a charitable donation of $236 million which netted them a $38 million tax saving.

The ICF is directed by 12 board members (5 Regional Districts, 5 First Nations & 2 Directors at large) representing the Districts and First Nation lands of the Corridor, which manages the rail line, land and assets worth about $337 million in the public interest.

Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway Map, 1912 (Photo: pkdon50 CC BY 2.0)